Come and find my new blog here.

On leaving Portsmouth

27 02 2012 So the headline is: we’re moving on. From September 2012, I will be Tutor in Pioneer Ministry at St John’s College Nottingham and Pioneer Minister and Priest in Charge in the benefice of All Hallows, Lady Bay with St Edmund, Holme Pierrepont and Adbolton (Diocese of Southwell and Nottingham).

So the headline is: we’re moving on. From September 2012, I will be Tutor in Pioneer Ministry at St John’s College Nottingham and Pioneer Minister and Priest in Charge in the benefice of All Hallows, Lady Bay with St Edmund, Holme Pierrepont and Adbolton (Diocese of Southwell and Nottingham).

I share this news with a mix of excitement, trepidation and sadness.

I am excited to be looking forward to a new role in a new place that allows me to develop as a theological educator at the same time as continuing and developing as a mission practitioner in an entirely new setting. I look forward to my mission practice providing a rich source for theological reflection with ordinands and others as I help them grow into their own forthcoming ministries. And I look forward to that theological reflection being a rich source for the shaping of an authentic and appropriate mission practice. The potential for an enriching interplay between those two components was what first attracted me to the role.

Ever since I was identified as a ‘potential theological educator’ through my ordination training, I have wanted to become involved in helping others learn, develop and be formed for ministry. I have had some small, but not insignificant opportunities to do a bit of that with STETS in the southern region that I have enjoyed enormously. This, and my own continuing academic study of theology at Masters level confirmed that this was an area I wanted to develop. That the Principal — Canon Dr Christina Baxter — and others at St John’s College have also recognised that potential and been willing to invest sacrificially in growing that nascent ability is hugely affirming and encouraging. This is an opportunity not to be missed. After Easter I will begin an informal programme of theological study that will help prepare me for my new role. Alongside that I will continue to offer some pastoral and liturgical leadership to the Sunday Sanctuary on a house-for-duty basis. Then in August we will move to our new home in Nottingham in preparation for the full start of my new role in September.

It is also a great opportunity to develop still further the integration of my twin passions of art and spirituality as I am called to engage with an area where arts and media professionals make up a significant proportion of the local population. There is a high proportion of young families too. It is an area where again I will be able to grow new forms of church and mission that bring all ages together to learn from and stretch each other spiritually.

I am daunted because in both aspects this role will demand even more of me than what I am doing now — and that’s pretty stretching! Quite honestly, it’s beyond me. I say that knowing full well that those who appointed me may well read this. But I don’t think they’ll be worried or think I deceived them at my interviews. Christian ministry is always beyond us — whatever particular gifts and experience one brings into it. Being stretched beyond ourselves goes with the territory. You either try and muster the resources from within and face inevitable burnout or look outside and beyond yourself to the source and ground of all vitality, love and strength. In this new role, as here, I will need to stay close to that source. So I am daunted not because I think I have to do it all myself but because I know that, in common with others, ego makes this a struggle.

It is daunting for all of us as a family to make a new life together away from familiar places, support networks and friends. This is truly new territory in all kinds of ways.

It is sad because we are leaving so much that we love behind.

I was not looking for a move. There remain great opportunities and challenges here in Somerstown and the centre of Portsmouth that would keep me stimulated, entertained and excited for many years to come. The Sunday Sanctuary has still much capacity to grow and evolve. The forthcoming union of the two parishes in Somerstown, as well as their shared aspiration to develop a new centre for worship and mission in the heart of the city, will ask much of the Christian community here in the coming days. There remains a need for compassionate visionary leadership. The city centre aspect of my role was only just beginning to become clear with great opportunities opening up for being a significant contributor to the cultural life and development of the city. Engaging with this process of discernment meant setting aside an exciting arts project that was really beginning to take off.

I am sad to be leaving behind work with two great schools in the area and relationships with their leaders that are not just professional but personal. The depth of trust and understanding that we have developed is a rare and precious thing. It will not be easy to say goodbye to these new and special friends and colleagues or their wonderful staff teams.

I am sad to be leaving behind a fragile but vibrant small community of new Christians and old that has been a source of unbelievable blessing, delight and friendship for our whole family. We will miss our friends — new and longstanding — terribly.

It is odd to be making this move so soon after writing on this very blog about how I thought this work needed someone prepared to be in it for the long haul. I have disparaged in conversation those agencies where people come for 3 years or less and then disappear. And yet I am doing the self same thing. This is a circle I am finding it nigh on impossible to square. Moving on does feel like a bit of a betrayal.

That is softened to quite some degree by knowing that I leave it all in the hands of a quite remarkable and outstanding colleague whom I am also privileged to call my friend. I don’t imagine how it could be possible to ever be so fortunate again as to be a partner in ministry and mission with such a gifted priest whom I’m sure will one day be called to high office in Christ’s Church. I will carry this experience with me wherever I go.

There is so much more to say — about the wider group of colleagues in cluster and deanery with whom I share in ministry and mission; about family and friends we’re leaving behind; about the sea when we will be so far from it; about the schools our children will be leaving behind; about this city’s fantastic (and troubled) football club and its passionate fans — but this will have to suffice for now. And this blog will in due course too have to draw to a close. It will not make sense to call myself the Pompey Pioneer once we are ensconced in Nottingham! But it will keep going for a while. Though it has necessarily been silenced through recent uncertain days, it will hopefully be a helpful record of a new Christian community and its guardian in transition. So even though the secret is out, I still invite you to watch this space…

Comments : 2 Comments »

Tags: mission, moving on, Nottingham, pioneer, Portsmouth, Tower block

Categories : Doing mission

The people walking in darkness have seen a great light. A homily for Midnight Mass.

24 12 2011Readings: Isaiah 9:2,6-7 John 1:1-14

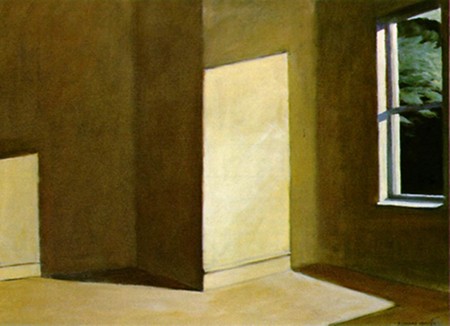

Since my early teens, I’ve been a fan of the American painter Edward Hopper. Lots of you will have seen his work in innumerable prints and reproductions. His most famous painting is called Nighthawks. It’s the one where you can see a couple enjoying a cup of coffee through the expansive window of an all-night cafe. Most of Hopper’s work is either in private collections or in the Whitney Museum of modern Art in New York. I thought it would be a long time, if ever, before I ever got to see the paintings in the flesh; or should I say in the canvas. But in the autumn of 2004, Tate Modern put on a major exhibition of Hopper’s work. And so finally I got to see the works I had admired for so long in reproduction, as they really were.

It was a memorable visit. Several things struck me about the paintings, that you could only see by seeing them up close. I’d heard it said and read it many times that Hopper was a poor draughtsman. I’d always resisted that idea. But seeing the canvases, I could deny it no longer. His drawing was definitely poor at times.

On the other hand, the strength of his composition was all the more apparent. But most striking of all was something that reproductions had hidden away. It was to do with Hopper’s treatment of darkness and light.

Lots of Hopper’s compositions have this dark, foreboding space within them. Those are often contrasted with the brilliance of the daylight in the East Coast of America where he lived and worked. When you see these paintings as a poster or in a book, the dark colours look solid and impenetrable and the light at its most brilliant is nothing more than the whiteness of the paper on which the image is printed. But when you see Hopper’s original canvases, something startling is there before you: Hopper’s darks are thin. The blacks, blues and greys that look so solid when reproduced, are just layers of thin turpentine washes. It’s as if they are veils through which the light might break through at any moment.

And the light.

The light is solid, thick with heavy, impasto paint. Even where it only touches the edge of a doorframe, the corner of a wall, it is a solid, tangible, real presence. It literally reaches off the flat surface and out into space. It extends out of the imagined world of Hopper’s pictures and into the reality of the viewer.

Those pictures that had seemed for so long to me to be about the proximity and presence of darkness, seemed suddenly to be about the overwhelming reality of light.

Light and darkness are of course real things in our experience. And they are real things that Hopper is representing in his paintings. But I think these paintings, just like our readings today, are about more than just sunlight and shadow. Light and darkness are metaphors for our human experience. They stand for hope and despair. And so often, it seems to us in our daily lives and in the world around us that it is the darkness that is real and solid and the light that is a thin illusion.

That is how the Judaeans living in exile in Babylon felt. And it is how the Jewish people living under the Roman occupation felt. These are the realities of darkness that our readings address today. But they have a wider vision too. They speak to every human person and society in every place and time.

The darkness is all around us and the darkness penetrates our being: the darkness of despair is within us. It seems to us more real, more present than the light of hope. That seems to us, especially if we find ourselves in the grip of that terrible illness of depression, like a faraway illusion, a vain yearning. The darkness can feel overwhelming. Hope can evaporate. Even the smoldering wick is eventually dim and cold.

But it is the darkness that is an illusion. It is the veil that hides the deeper and more real reality of Eternity. And in our readings tonight, we are reminded that the Real has broken through. The veil has been ripped open and shown up the darkness for what it is.

The brilliance of God’s love has broken through the darkness of human cruelty and the bitterness of despair. And so it is that great light, and not darkness, which is more real. There is nothing in our lives, our world, our universe that is so bleak, so dark, that it cannot be transformed if we open our eyes to the reality of God’s love.

We do not have to do escape from the darkness by our own efforts before we can see it. The light comes to us in the midst of our darkness. It shines among us. It shines on us and reveals that tarnished as we may be, we are made to reflect it. Because the light comes to us as one of us. We see the light of the eternal God in a human face.

He didn’t appear in the brilliant glory of a Roman emperor, or a Judaean monarch. His appearing showed up those fake lights for what they were: the deepest darkness. The brilliance of God’s glory illuminated our most fragile humanity. He came to us as a baby, born to refugee parents in desperate poverty.

And so here, where the darkness seems deepest, most threatening, most ready to overwhelm us, here is where the light is shown to be most real, most present. Here is where the brilliance of the deeper reality of heaven breaks through the thin veil of darkness. And all the blinding glory of heaven’s appearing to shepherds on a hillside is but a faint reflection of the Great Light that those same shepherds saw when they encountered the newborn baby tenderly wrapped and laid in a feed trough.

Just like the thick presence of light broke into my consciousness when I saw those Hopper paintings in the flesh, so we encounter the eternal reality of God in the flesh in Jesus – born in Bethlehem, living in Nazareth, dying and rising in Jerusalem. What has been mere reproduction, poor copy, faint echo, pale reflection in the words of prophets, recorded on scrolls, recited in religious ritual is now before us: living, breathing, dying, rising.

God. Is. With. Us.

—–

But that was all long ago.

The exhibition is over. The paintings have been taken down, packed away, shipped back to the place from which they came. I must rely once again on reproduction and memory.

And what of Christ’s advent? What of God’s coming into the world? Joseph and Mary, shepherds and magi encountered his real presence. They could see him, smell him, hear his breathing, touch his delicate skin. Are we to live only with that scene’s reproduction in the words of evangelists and imaginations of artists? Are we to live only with the handed down memories of others? Or can we too know the Real Presence of that Great Light in the midst of our darkness too?

We can.

We can know that light as a living presence, as the true reality in our lives each day. For he lives still.

The Great Light has shone in the darkness, and though it did its utmost to extinguish it, the darkness could not overcome it. Even the grave could not extinguish him. Christ has died. Christ is risen. Christ will come again. We look for Christ’s coming in future days.

But we look for his coming today. We look for his coming in our hearts, by faith. And we look for his coming among us as we break bread and pour wine.

The Real Presence of God’s unquenchable light is among us. We know it as we see it reflected in each other’s eyes as we gather around the table to which he himself invited us. We ask him again to be born within us and among us tonight:

O holy Child of Bethlehem, descend to us, we pray;

Cast out our sin, and enter in, be born in us today.

We hear the Christmas angels the great glad tidings tell;

O come to us, abide with us, our Lord Emmanuel!

Comments : Leave a Comment »

Categories : Uncategorized

I will try to fix you

5 12 2011My last post was a look at one of the questions raised by the idea of relational mission: what’s our motivation? What is underlying our desire to befriend people? This is some further musing on the same question. But this time I’m looking at it from another angle – what have the people we have befriended gained from being our friends?

I guess I’m challenging the unspoken assumption that getting to know ‘us’ is a good thing. In all the Church’s talk about mission, it’s taken for granted that our outreach to new people not currently connected to the Church is beneficial for those new people. That’s a theological assumption, I think. But if we no longer believe that we take God to where God is not (which, thankfully, we don’t) what ‘goods’ do we bring? And dare we test empirically how good it really is for people to interact with the Church? For whose benefit is that interaction, really? For those with whom we interact or for ourselves?

We are at least in part motivated I reckon by wanting to see the Church grow. Why? To shore up our own fragile faith by persuading others to share it or by temporarily fending off the decline that so sorely tests our confidence? Sound cynical? It is a bit. If we believe we really have good news it would be selfish to keep it to ourselves. But at the same time we need to recognise that our proselytising tendency can be experienced by others as a threat, particularly if they are of another faith background or are avowedly secular or humanist. While others might be prepared to say that those people are just plain wrong, I am not. We have to share this world. We need to find ways to peacefully co-exist. That means I think according people a high degree of dignity and respect and taking their views seriously. That means putting ourselves in others’ shoes. For me that means being prepared to ask whether, from the perspective of, say, a secular humanist, we might ever be viewed as a positive presence. So again I find myself asking: what ‘goods’ do we bring?

I was having a conversation recently with someone who used to work in retail. They were telling me the story of a retailer who tried to grow their business by increasing the sale value of each customer interaction. The net result of all their action was that the business stayed exactly the same. Setting out to grow the business resulted in stagnation. The concentration on what the business wanted from the customer interaction did not allow that business to meet its aims. When, instead, they focused on what their customers wanted from their interaction with the business, the business grew.

That’s an anecdote and not careful research. But it does suggest that the Church will fail to achieve its desired growth if that is what it thinks about. Instead it hints that concentrating on the people with whom the Church interacts, considering their needs and desires, will be the only way that growth can happen. It’s only while we’re looking the other way that growth can occur. That’s a pretty bold statement and it’s based on pretty flimsy evidence. But surely that is what we’re all about. No, not bold statements based on flimsy evidence. Though that is something of which we’re often accused! I mean putting others first. We should be seeking to generously strive for the benefit of others as an end – the end – in itself, not merely as a strategy for achieving our organisational goals.

Some will argue, I guess, that wanting the Church to grow is for the benefit of the (capital ‘O’) Other. It’s for the ‘Glory of God’, whatever that means. But the Christian story surely makes clear that God is always out for the benefit of the (lower case ‘o’) other (even if some parts of the Bible are a little more difficult to reconcile with that proposition).

I wonder if you can see what I’m getting at? If you can, you might be able to help me because I’m not quite sure! I think I’m just trying to push the question of motivation all the way – in this instance in non-theological terms. Why? Because I think we have to at least try to imagine what it might be like to encounter a community of people that, to some degree, have an agenda that includes seeing you change. The Church is not unique in that but it’s there. That doesn’t mean it’s all about progress. It might mean – it pretty much does for some church members here in Somerstown, I think – that people with insurmountable mental health or addiction problems at least find a place to belong and to find companionship in the midst of their struggles.

But [finally he gets to the point] what has it meant to the newer members of the Sunday Sanctuary to encounter this fragile community of Christians and become part of it? How has that been good for them?

I haven’t really asked. But others have. These are not desperate or broken people we’re talking about, at least no more desperate or broken than the rest of us. So we haven’t fixed anyone (as if we could). The sense I have is that our new friends, like the rest of us have found a deeper and growing sense of belonging, self-esteem and purpose. And they, like us (these distinctions seem so empty of meaning now) have found new friends. We are all discovering a wider – yes theological – framework in which our being, our living and dying, our meaning and our place in this universe make a bit more sense. For some reading this, of course, that framework is inherently delusional and so cannot be a ‘good’ but I do beg to differ here. We are inhabiting, a little more deeply and in some subtle and unexpected ways, the idea that – to borrow the title of Rob Bell’s book – love wins. We’re aligning our lives as individuals, as families and as a whole community with the idea of that gentle victory, just a little more each week. I think in a tiny, tiny way, that’s making the world a little bit of a better place. That’ll do for me.

Comments : Leave a Comment »

Tags: community, failure, growth, mission, missional, relational, success

Categories : Doing mission

I’ll be your friend Roland

25 11 2011 Now I’m really showing my age! Anyone else out there remember Roland Browning off of Grange Hill? He was the fat lad that all the bullies picked on in the BBC kids’ TV show in the 80s. However hard things got for Roland, he was never quite desperate enough to take up the offer of friendship from Janet St Clair. Janet’s catchphrase on the show was, ‘I’ll be your friend Row-land’. At least I think it was. Maybe it’s one of those catchphrases that people never said, like, ‘Beam me up Scotty’. Anyway, the point is that however desperate you get, there are some people you don’t want as your friends. It’s less embarrassing to be a Billy-no-mates than to count some people among your mates.

Now I’m really showing my age! Anyone else out there remember Roland Browning off of Grange Hill? He was the fat lad that all the bullies picked on in the BBC kids’ TV show in the 80s. However hard things got for Roland, he was never quite desperate enough to take up the offer of friendship from Janet St Clair. Janet’s catchphrase on the show was, ‘I’ll be your friend Row-land’. At least I think it was. Maybe it’s one of those catchphrases that people never said, like, ‘Beam me up Scotty’. Anyway, the point is that however desperate you get, there are some people you don’t want as your friends. It’s less embarrassing to be a Billy-no-mates than to count some people among your mates.

I think Christians are to the rest of the world what Janet St Clair was to Roland Browning – the people who want to be your friend; but you’d rather boil your own head than be seen anywhere near them. That has to be remembered, I think, when we talk about making friends with people. If we encounter a certain reluctance from people when invited to our soppy events, that may be magnified when we try and be their friends. First you have to persuade people that you really are quite normal, or at the very least that your lunacy is more like theirs than they’d ever really imagined.

There is a serious point here. I think people are suspicious of Christians trying to be their friends because they think there’s a hidden agenda. ‘You just want to be my friend so you can make me join your church.’ It’s an understandable suspicion because it’s, at least partly, true. What does it really mean to say that mission and ministry are going to have be relational? Lots of things. But translating it into everyday speak, it sounds very much like ‘make friends with people so that you can tell them about Jesus’.

Doesn’t everyone have an agenda? The drug and alcohol worker I talked about yesterday wanted to work relationally. Translation: I want to befriend people so that I can get them off drugs and alcohol. People not keen to get off drugs and alcohol might not want very much to be befriended by a drugs and alcohol worker with targets to reach.

If this sounds negative, I don’t mean it to. I just want to temper what I’ve been saying in the past couple of days with some realism and to encourage myself and maybe you too to put yourself in the shoes of someone who might be the subject of my/our efforts to befriend. Relational mission inevitably means that there is an agenda behind crossing social divides and making friends. Members of the Church will do that to some extent because they want to share their faith.

But that doesn’t have to translate into instrumentalism. We don’t have to see making friends as a means to the end of evangelism. That is how people have experienced their interaction with Christians. Some Christians lose interest in people who don’t quickly make some grand profession of faith. Truly relational mission must involve a commitment to love and care for people whatever their response to our faith. Sharing our faith will involve giving an account for the hope within, talking about our experiences, not preaching. But it must also include responding to people’s real needs with real practical love and care. And here’s the nub: being prepared to receive both those things too: listening to people’s real experience and allowing them to care for us too. Without that, we patronise people. We meet them as ‘clients’ imagining ourselves in a position of superiority – having the ‘goods’ people need – rather than engaging with people as fellow human beings. That means recognising and accepting that we have as much to receive as to give and that in the end the only resources we have to bring are ourselves. All we have to offer is who we are.

That’s a world away from thinking that we, charitable, middle-class people, will out of the goodness of our hearts give the poor people of this working class area what they need. But in offering ourselves, I think we do bring something unique. First of all, who we are is (however imperfectly) shaped by the Christian story that we inhabit. Whatever truth there is in that story will not be communicated by argument and persuasion; it will communicated only by who we are. Secondly, in offering ourselves in real friendship, that anticipates receiving as well as giving, we honour, respect, value and love people in a way that few others do. It’s a way of expressing our belief in people. It’s a way of saying: ‘You’re worth getting to know’.

Comments : 1 Comment »

Tags: exploitation, friendship, gospel, hidden agenda, mission, relational, relationships

Categories : Doing mission

All of rabbit’s friends and relations

23 11 2011 What does ‘relational’ mean? It’s a word I used in my last post. It’s a word that gets bandied about a lot in blogs like this. I’ve heard it many times at the sort of church conferences and workshops I frequent. I’ve used it in conversation innumerable times. But is it just a buzzword? A sort of linguistic bandwagon onto which I have uncritically jumped?

What does ‘relational’ mean? It’s a word I used in my last post. It’s a word that gets bandied about a lot in blogs like this. I’ve heard it many times at the sort of church conferences and workshops I frequent. I’ve used it in conversation innumerable times. But is it just a buzzword? A sort of linguistic bandwagon onto which I have uncritically jumped?

Probably. A bit. But it has come to have some real content for me in recent weeks as I’ve reflected on our adventures in mission over the past two years.

Its meaning and implications really crystallised for me in a conversation with a drug and alcohol worker. I wasn’t the client, before you ask. I had been speaking at this person’s church. After the service they told me about their frustration with their work. Imagine yourself in their situation. You work three days a week. One of those days is taken up with paperwork. On the other two days you have a caseload of more than twenty clients. You can see how it would go. You’d never be able to do much more than a cursory monthly meeting with each of your clients. All you could do is to monitor progress, if there were to be any, any real support or intervention would be incredibly difficult, not to say impossible, to achieve.

Now imagine that you can work as this person really wanted to – relationally. Imagine your caseload is cut down to three or four people, maybe even just two or three. You can invest real time with people and build up a level of trust and understanding that are currently impossible to achieve.

The personal risk and cost are much higher, of course.

First of all you’d have to sacrifice your contact with 18, or 20 people from among your current clients. But what good are you actually doing for/with them? And in saying goodbye for now, you’re not necessarily saying goodbye forever. You’re focusing your energy on where you really might be able to make a difference and not spreading it so thinly that you can realistically achieve very little of value. And you might be able to get to some of those others in time.

Secondly, you’d be taking a much higher risk in terms of the potential for your efforts to fail to achieve a positive outcome. With a big client list, where you can achieve a very limited amount, you can at least spread the risk of failure and your measurable outcomes will, of necessity, be more modest. If you invest everything in a small number of people, you might expect (or at least your paymasters will expect) much more dramatic outcomes. The failures will be much more professionally and personally costly; professionally because your reputation suffers; personally because if you have any real empathy (and why would you do this sort of work if you didn’t?) your clients’ failures will really hurt you.

That’s the sort of approach I think has been developing in my ministry and in the life of the Sunday Sanctuary

. It’s less about trying to create something that will be a catch-all and draw in lots of people with whom we have minimal contact (if that were even possible) and more about investing focused time, energy and resources on a small number of people.

There’s much more to say about this. What does it imply about our motivation for befriending people? What are the implications for our community life? What does it actually mean? Or to use a well worn cliché – what does it mean where the rubber hits the road? These are some of the questions I’ll be pondering out loud on this blog in the coming days.

Comments : 1 Comment »

Tags: families, mission, relational

Categories : Doing mission

A beautiful failure

22 11 2011 It has been two years since the congregation formerly known as St Luke’s in Somerstown (in the heart of Portsmouth) moved out of its building and began gathering instead in one of the nearby tower blocks. On Advent Sunday in 2009, with the Bishop’s permission, we ceased Sunday services and opened instead what we have called the Sunday Sanctuary. This wasn’t simply the relocation of our services to another place. We went right back to almost nothing. We had breakfast together and invited residents of the tower block (mainly young families) to join us. We imagined that the typical encounter would involve a bite to eat, a chat and maybe something a bit hands on and – with a light touch – spiritual. Maybe people would stop for 20 minutes or so.

It has been two years since the congregation formerly known as St Luke’s in Somerstown (in the heart of Portsmouth) moved out of its building and began gathering instead in one of the nearby tower blocks. On Advent Sunday in 2009, with the Bishop’s permission, we ceased Sunday services and opened instead what we have called the Sunday Sanctuary. This wasn’t simply the relocation of our services to another place. We went right back to almost nothing. We had breakfast together and invited residents of the tower block (mainly young families) to join us. We imagined that the typical encounter would involve a bite to eat, a chat and maybe something a bit hands on and – with a light touch – spiritual. Maybe people would stop for 20 minutes or so.

We had no idea whether anyone would come. But come they did. And those who came did not come for a brief visit. They came in the moment we opened the doors each week, stayed with us all morning and before long, unbidden, got stuck in with clearing up at the end of the morning. This very different sort of engagement than we had imagined meant we very quickly had to give the morning more structure and shape. It threw us back on the liturgy. What we do together now has the skeleton of an Anglican Eucharist – we gather over breakfast; we set aside all that we regret from the past week; we collect our thoughts and prayers; we share a story and reflect together on its meaning for us today; we look out to the needs of those around us and the wider world; we give thanks; we share bread and grape juice and we ask God’s blessing as we go on. Though the flesh on the bones might not be so immediately familiar, there is a family resemblance with our sister churches in the Church of England.

As I reflect on the past two years, and what we’ve learnt together, I am bound to ask: has it been a success?

That, of course, depends on what you mean by success. I think we set out on this journey with a little bit of a Field of Dreams mentality: ‘if you build it, they will come’. (That’s a misquote I know but I hope you’ll excuse a little creative license there.) I think we set out with the idea that if we changed what we do together; changed where we do it and changed who we invited to come, that we would make some sort of breakthrough in Somerstown and in particular in the block of flats (Wilmcote House) to which we had relocated.

In those terms, the Sunday Sanctuary has failed.

We have failed to make a big breakthrough in Wilmcote House or in Somerstown. We have engaged with a small number of families in the block, some who have stayed with us and others who have moved on after a little while. But most of the young families in the block pretty much ignore us.

Maybe our ‘offer’ is wrong. We insist on children coming with at least one grown up. We are running a family gathering in a place and at a time when a significant number of parents just want their kids out of the way or off their hands. We had a suspicion from the outset that a kids’ club would be overwhelmed. We had neither the people nor the resources to sustain something like that. So we set ourselves the parameter of barring unaccompanied primary- and pre-school age children at the very beginning. That has proved very difficult at times. I have hated having to turn away kids that are desperate to come in.

But even more fundamentally, I think, the biggest flaw in our thinking is that we were still ultimately operating an attractional model of mission. We were still creating an event that we expected people to come to. We made it as easy as possible for people to come – especially by moving ourselves much closer to where they live. But it still relies on people responding to an invitation from strangers to come to an event they know little about.

So though we took a massive step out of our comfort zone, I still don’t think we fully inhabited Jesus’s radical sending of his disciples to be guests, reliant on the hospitality of others in hostile territory.

As an initiative, then, in terms of measurable outcomes, it has failed.

But what a beautiful failure.

I write this a couple of days after we baptised five members of our community. Of those (four children and one adult), only one came from a family that I think would have explicitly defined themselves as Christians a couple of years ago. And as I write this I am looking forward to seeing six more members of our community confirmed at the cathedral. People whose connection to Christian faith has been very basic and tenuous have discovered a lively faith for themselves.

We have grown in numbers in a small way. We’ve also lost some more longstanding Christians. Some were not able to cope with being so far out of their comfort. Others have simply relocated. So we are not much bigger.

That is so often the measure by which people – consciously or otherwise – judge whether something has been a success. I hinted at it myself earlier by talking about a ‘big’ breakthrough. And on those terms, we have just about stayed steady. We have failed to achieve numerical growth.

But our growth in depth has been marked. Those longstanding Christians who have been able to stick with it have grown in faith as they’ve engaged with new people in an unfamiliar setting. Newer members who had only the most nominal faith have reached a point where they are making a public commitment to live as a Christian. We’ve all grown in the breadth of our spiritual experience as we’ve moved closer to becoming united with our sister parish of St Peter’s.

But above all we’ve grown in the depth of our relationships. The newer members aren’t people who’ve joined us any longer. They are us. We have become one family.

There are lots of things we’ve learnt through this whole experience.

First, I think we’ve been reminded of something we already knew, even explicitly remarked upon. People in this place don’t come to stuff. It’s not a matter of tweaking our event to get it just right and then people will come. They won’t. They’re not interested. They don’t care what we have to say. Maybe we could cast our net a bit wider (leaflet all the tower blocks instead of just one) and maybe we’d get one or two more families like the lovely ones who found their way to us and became part of us. We will probably do that. But the fundamental and stark reality still holds. If we build it, they will not come.

Second, we can’t look to the handful of local families who are part of our community to reach their neighbours all by themselves. That’s because they are not the hard to reach, troubled families. Those who have joined us are really nice, together people. If that sounds judgemental on the rest of the families around, I’m sorry. But most of us know what we mean by ‘nice’ people. These are they. Sunday Sanctuary really was a sanctuary for them from the troubles and menace around them. It would take incredible courage, confidence and faith for these brand new Christians to reach out to the most challenging of their neighbours.

Third, that means this is no ‘hit and run’ sort of ministry for me. The idea I started out with that I could spend about three years here and, during that time, get something off the ground, train up local leaders and then move on to the next place (I really thought this!) – well that just seems laughable now. I am going to have to be here for the long haul.

Finally what has dropped like a great big penny is that ministry here has to be relational. Again, I’ve said that before. Right at the outset. But I’m only just beginning to understand what that means. What we’ve discovered, because this is what’s actually happened, is that if we’re going to make a difference in Somerstown, it will be one family at a time. It will be about investing in real friendship – giving time, attention, love and practical support to a small number of people at any one time. It’s like the old story of the little boy throwing starfish back into the sea after a storm. The beach is covered in starfish as far as the eye can see. A man says to the boy: ‘how on earth do you hope to make any difference?’ Picking up another starfish, and casting it back into the safety of the sea, the boy says, ‘made a difference to that one.’

Comments : 4 Comments »

Tags: Advent, attractional, baptism, Children, church, failure, friendship, mission, missional, relational, sent, success, Tower block, Wilmcote House

Categories : Discernment, Doing mission, Missiology

Parked

19 05 2011 I have finally admitted defeat. Finishing my MA studies means that this blog is effectively parked until after the summer break. I hope you’ll come back and read it again then. Thanks for your patience. 🙂

I have finally admitted defeat. Finishing my MA studies means that this blog is effectively parked until after the summer break. I hope you’ll come back and read it again then. Thanks for your patience. 🙂

Comments : 2 Comments »

Categories : Uncategorized

Enjoying the silence?

4 02 2011Sorry to have gone all quiet this week after last week’s burst of writing. I am trying to finish an assignment for my MA. It has to be in on Tuesday. It’s a Hebrew Bible module. I’m writing about historiography and in particular whether it’s possible, necessary or desirable to construct a history of Israel on the basis of the Biblical texts. Don’t think I’m going to say anything particularly ground-breaking. Essentially I think the actual history of Israel is very difficult to recover but that we should read the Bible as literature and look for meaning in the narrative. Whether they existed or not, the events, places and people are always cyphers — a vehicle for the theological concerns of those who compiled the historiography. But that doesn’t mean they’re not profound or sacred.

Comments : 2 Comments »

Tags: assignment, MA, study, writing

Categories : Stuff and nonsense

Enjoy the silence

26 01 2011So yesterday I wrote about listening to the radio less. This is essentially about reducing the amount of background noise, both sonic and intellectual. But toning down the wallpaper is not the same as knocking a hole through to the other side.

So what have I done to actually make time for silence?

Well I think it’s fair to say that I’m working my way into a daily and weekly rhythm that includes time to be intentionally still. Each morning, my colleague and I spend twenty minutes in silence as part of our morning office. And before Christmas I was more and more reliably including a midday office with ten minutes of silence and night prayer with a further twenty minutes. Over the Christmas break, I let it go. And it’s been more difficult to reinstate since coming back. I’ve been struggling more with another old habit – staying up late.

So it’s a work in progress, but I think there is real progress.

I’m realistic about where I’ve got to, but I’m approaching this with a sense of joy and freedom. I am not experiencing a ‘hardening of the oughteries’! It’s in response to a sense of invitation and call that I am engaged in this journey, not duty.

So what difference does this make?

Perhaps first I’d better reflect on what the experience of reasonably frequently (I can’t quite yet truthfully use the word regularly) spending time in quiet has been like. I know this is a well worn path. Many have been this way before. And my experience has been very similar to the little I’ve read of others entering into a contemplative way of life.

The first word one has to speak is ‘distractions’. We are so trained by our lives to live either in the past or the future that the mind very quickly wants to inhabit that territory. It’s difficult not to go over some incident that has been. Or to start to plan something that is to come. The ironic thing is how often those thoughts are about how I will share with others the beauty of silence and stillness!

You might notice, though, that I haven’t used the words ‘struggle’ or ‘frustration’ in reflecting on that. It seems to me that so much of our lives is cramming stuff into our consciousness (and in me thereby fermenting this sense of near dread that there’s something I’m missing). It’s not unreasonable to expect that given a bit of space, some of the excess of psychic noise will begin to bubble up and out. (I use the word psychic here in its psychological rather than parapsychological sense.) So I actually see this as a positive thing. That doesn’t mean I let the reviewing or planning instinct take over. I try to acknowledge it and draw myself back to simply searching for stillness.

The way that I do that is again very well known. I repeat a simple phrase or word in my mind, in time with my breathing. Mostly I use the Jesus Prayer: ‘Jesus Christ; Son of God; have mercy on me; a sinner’ or occasionally: ‘in God I live and move and have my being’ or as in Advent: ‘mar-a-na-tha!’ (one of those deeply mysterious Aramaic words we generally equate with ‘Come, Lord Jesus!’). That does allow me to re-centre when the mind wanders.

It’s out of that experience, partly, that I have sought to reduce the level of ‘noise’ with which I surround myself (hence listening to the radio less, watching a bit less TV).

The other thing to say (again?) is that stillness is a better word than silence. It would be difficult to achieve with huge amounts of external noise, but on the other hand, true silence is not possible. There’s always the noise of the rain, or the hum of the fridge, or the sound of a car door being slammed, or birdsong. The essential thing is not to tune it out but to gently suppress the sort of categorisation I’ve just done. To be present to the unique sonic qualities of each vibration, without naming what it is. It’s about the unique gift of each sound actually being a doorway to being present to the immediate present moment.

And sometimes, just sometimes, I am brought into a deep sense of inner stillness, calm and presence.

So what difference does it make?

It doesn’t make me one of those annoying, superhuman, people who never lose it, are never phased or upset or worried. But there is a just emerging sense for me that there is a still centre to my being and that in that still centre I connect with Being and that there I am loved; utterly constantly and faithfully loved.

Comments : 1 Comment »

Tags: contemplation, distraction, love, prayer, rhythm, rhythm of life, rule of life, silence, Spirituality, stillness

Categories : Spirituality

Recent Comments